The characteristics of illicit traffic in cultural goods

Unlike the traffic of drugs, weapons or chemicals, the illegal transnational trade of cultural goods concerns a product that is usually considered licit. Moreover, this traffic is often seen as a harmless crime and is hardly remarked upon by law enforcement agencies, governmental authorities or the public, despite its size and its obvious monetary value.

As for the trafficked objects, they are hard to identify. Cars have brands, models, year of production, etc. Cultural objects were produced in the distant past, sometimes in series, but sometimes with unique and identifiable characteristics. Moreover, many of them, and obviously all the unexcavated archaeological objects, are not inventoried.

Furthermore, the value of the goods increases with uniqueness and time, with some items missing for decades before emerging on the legal market. This time extension can disrupt the investigation undertaken by police officers.

"Man with a Skull", stolen in 1968 in Sibiu, Romania, recovered in 1996 in Florida, USA.

Finally, the fight against illicit traffic is often constrained by a series of legal weaknesses which diminishes the ability of law enforcement agencies and prosecutors to fight looters and traffickers of cultural objects:

- The main international legal instruments are rarely fully implemented.

- In many countries, theft, concealment and illegal excavations are not considered as serious crimes.

- Penal sanctions are unfortunately very light in a large number of countries.

- Short time limitations make the legal recovery of a stolen object that much more difficult.

- Few countries have specific import procedures for cultural objects.

- Short deadlines for seizing complicate the work of customs officers in identifying tainted objects.

The supply and the demand

As with all other types of traffic, there is a very real link between supply and demand, with obvious consequences on the value of the item trafficked. Nevertheless, the market is not always ruled by a predictable pattern, and the supply, the demand and the value of an object are not necessarily connected.

In some cases the traffic of an object is not motivated by the demand (impulsive, occasional or opportunistic thefts, art-knapping, etc.) and criminals are sometimes completely unaware of the value of the object they are excavating or stealing.

For the other cases, the supply is mainly determined by the number of similar goods produced and the opportunity to take possession of them. However, sudden and important variations in the supply can happen in extraordinary circumstances such as natural disasters, civil unrest or armed conflicts.

On the other hand, the demand can be determined by a wide range of different factors, among others: the uniqueness of the piece or – on the contrary – the abundance of specific items; the popularity of the artist; the artistic, cultural, symbolic, scientific and historical value of the item, etc.

Monet's Charing Cross Bridge, London, stolen from the Kunsthal Museum (Rotterdam) in 2012. Photo: Wikipedia

A typology of the theft

Establishing a strict typology of the illicit removal of a cultural object can be complicated, but case studies have allowed to draw three main patterns:

Targeted thefts or illicit excavations:

It is the targeting of a specific item or a type of item, sometimes upon special request or to meet a demand from the market. In some cases, the looters or thieves only have an approximate value of the item. This is especially true in cases such as the theft of all the manuscripts from a specific section of a Library, or the looting of a single part of an archaeological site.

Targeted thefts in places of conservation have the same characteristics as a “traditional” burglary in terms of the number of people involved, the methods, the length of the operation, the number of items stolen. The occurrence of such crimes highly depends on the level of security in the place of conservation. If the success of these operations often requires skilled criminals, they can also be committed by unexperienced criminals and involve people from inside the robbed place.

Targeted excavations involve a limited number of experienced people, using materials such as metal detectors. The Tombarolo or other kinds of treasure hunters are the perfect example of targeted looting of sites. Despite the sometimes high value of the looted objects, the criminals are not necessarily driven by financial motives and remove objects for their historic and symbolic value. Heritage and art professionals can be involved in such operations, either being behind or actively participating in these illegal excavations.

Objects can also be removed for the value of the material they are made up of: ivory, gold, etc.

Treasure hunter using a metal detector. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Massive thefts or looting:

The second type is the massive theft or looting of cultural property, with sometimes neither knowledge nor consideration for its value. In the case of excavations, they are very harmful to scientific and historical research since the archaeological context is sometimes entirely destroyed with the disappearance of the objects.

Massive excavations or looting of places of conservation can involve unexperienced people in large numbers. They are logically more likely to happen in contexts of crisis: civil strives, armed conflicts or natural disasters. The illicit excavation of the Syrian archaeological sites during the armed conflict or the looting of the Baghdad museum in 2003 are amongst the most famous examples illustrating large-scale illicit removal of cultural property.

The Syrian site of Apamea, before (2011) and after (2012) its massive looting. Photo: Trafficking Culture

Opportunistic or occasional theft:

Finally, the less predictable but however common kind of theft actually consists in two similar yet very different trends: the opportunistic theft and the occasional theft.

The occasional theft is a single and hardly predictable event, which can be committed by a person normally considered as being innocent. The opportunistic theft has the same characteristics, though it is also an unplanned crime, which is firstly driven by the readily available opportunity to take possession of an object without risk. Opportunistic thefts represent a large proportion of the inside jobs. The example of the curator stealing one precious item of his museum’s collection after 20 years working in the institution perfectly illustrates it.

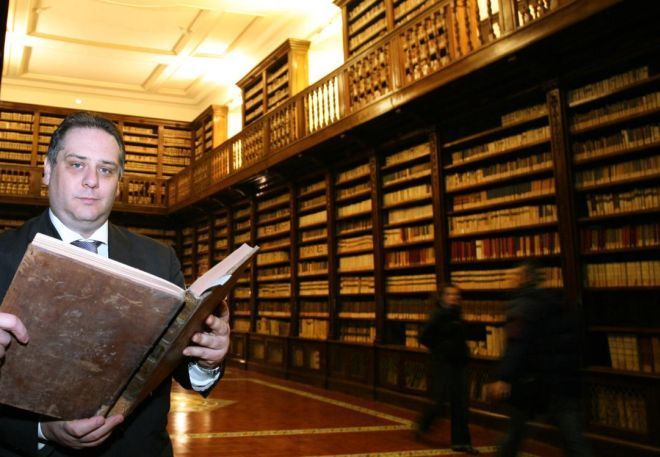

Marino Massimo de Caro, former director of Naples’s Girolamini library, convicted for the theft of more than 1,000 books from the institution. Photo: The Art Newspaper

The transportation

It is hard to draw a precise network of the international circulation of stolen objects, even though law enforcement agencies are aware of the shape of the most famous routes for the traffic. The development of such networks is partly based on the opportunity factor, which can be detailed as follows:

- The pre-existence of a circulation route

- The possibility to transport the object with a minimum risk of being caught (it often determines the choice of transit countries)

- The opportunity to sell the object on the black market

There doesn’t seem to be a preferred means of transportation for the illicit traffic of cultural goods. Though road transportation is not subjected a priori to a close control from national law enforcement agencies, the number of seizures made in airports and harbours clearly indicates the difficulty to control the transportation of cultural objects, particularly at the border checkpoints. Logically, the means of transportation and the type of vehicles differ according to the type and the number of objects transported.

Destination of illicit objects

Should they stay in the “black market” (even though the concept of black market in this regard is uneasy to define), stolen or looted cultural property can end up in the hands of a wide range of different final buyers. In the case of special orders, the objects can be destined for the collection of the person who actually ordered and sponsored the theft. Though, in most of the cases, they are purchased by private collectors highly experienced in the black market. Occasionally, potential buyers of tainted objects can also be targeted by the criminals. Often unexperienced, they can be completely unaware of the legal requirements concerning the acquisition of a cultural object.

Along with individuals, museums and places of conservation can unfortunately purchase stolen cultural objects. Even though the situation has dramatically changed in the past 10 years, notably due to the reinforcement of legislation, and the dissemination of ethical rules and professional standards, efforts remain to be done in order to prevent heritage institutions from participating, even unintentionally, in the illegal trade of cultural objects.

The last destinations for tainted objects are the “intermediary buyers”. Private sales, auction houses (including online sales), art galleries and antiques are ideal places for the buying and selling of objects with fraudulent origins. Although improvements have been made in controlling the art market, the legal framework regarding acquisition procedures remains quite weak; and in the absence of strong ethical rules, self-regulation still prevails in the sector, particularly for small or on-line companies. In this context, a number of intermediary actors knowingly buy stolen cultural property and sell them to unscrupulous buyers.

Even though it is a still an infrequent situation, cultural objects can also be stolen not to be collected or sold, but for the purpose of art-knapping, which consist in stealing a cultural good and asking for a ransom in exchange for its return to its rightful owner.

Dacian gold bracelets, looted from the Sarmisegetusa Regia Dacian fortress. They were recovered on the international market and returned to Romania. Photo: Wikipedia

The insertion into the legal market

A large number of looted or stolen objects often leave the black market to be offered for sale as “legal” property. But they don’t always find their final destination that easily. It can take years, sometimes decades, for a tainted object to pop-up on the “legal” market, or to end up in the exhibition room of a museum or the living room of a private collector.

Nevertheless, before penetrating the legal market, “illicit” objects often need to undergo a range of operations to be laundered.

The legality of the ownership over a cultural object is usually determined by the supporting documentation (title of ownership, certificate of authenticity, history of the object, export certificate). Therefore, the faking or forging of documents is the most common method used to clean the past of an object, or even create a full fictional history for the item.

Consequently, in the event of a stolen object being sold on the legal market with fake documentation, it can be hard to question the legality of the ownership and claim its restitution. In such cases, and since the burden of proof often lies with the plaintiff, the claimant needs to prove the illegal nature of the supporting documentation. In this regard, it is of paramount importance to document cultural objects in detail in order to be able to prove its legal ownership.

In the absence of sufficient tangible evidence, expert advice sometimes remains the only option prosecutors have to make up their minds and determine the legality of the ownership. For all public administrations and law enforcement agencies, the role and position of art and heritage experts and professionals remains a sensitive matter, either by being directly involved in the sale or purchase of the item or by using their expertise to produce fake documentation.

One of the main problems is that the longer an object stays on the market, the more difficult it becomes to question its legal provenance. Firstly because of the problem posed by time limitations, secondly because the accumulation of transactions and successive owners confers a “story” to the tainted objects, and makes its legal ownership harder to question.

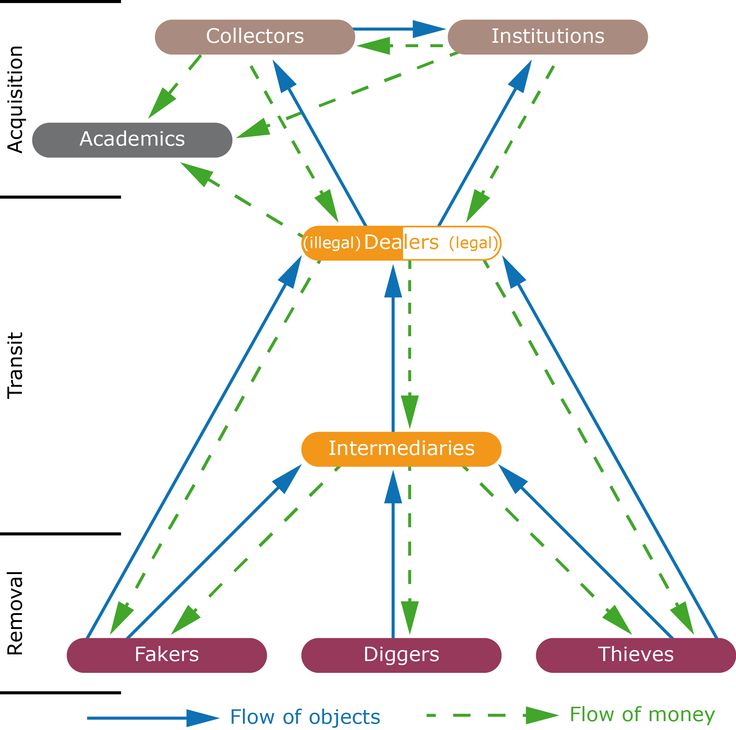

Figure showing the circulation of money and objects between the different actors of the traffic. Source: Neil Brodie

Glossary: acquisition, archaeological object, archaeological site, auction, authorisation (of export), certificate of authenticity, conventions, cultural good, cultural object, documentation, export (of cultural object), export certificate, fake / forgery, illicit excavation, illicit import, illicit traffic, import, inventory / registry, looting, ownership, provenance / provenience, restitution, statute of limitation / time limitation (time limit), valid title