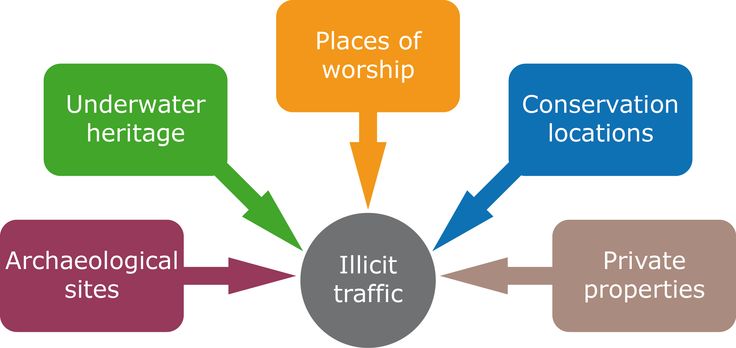

The question of where illicit traffic occurs can be divided into two parts: “Where are the objects taken from?” and “What countries or regions are most involved and affected?”

The answer to both questions is more complex than one might think. Theft of objects can happen in different locations: archaeological sites – including underwater –, public or private places of conservation (museums, churches, castles, houses, etc.)

The smuggling of objects out of archaeological sites is mostly due to a lack of appropriate protection, which can be explained by lack of funds, size and nature of the area to protect, and absence of inventory and safe storage of excavated objects, just to name a few. Countries with a great richness and diversity of archaeological heritage and sites are therefore highly exposed to illicit excavations.

The traffic of underwater heritage represents a particular and growing issue of concern. Shipwrecks and underwater archaeological sites are a very attractive target for looters, particularly for the quality of the objects excavated and the difficulty for national authorities to control their maritime areas.

Underwater antiquities. Photo: UNESCO

Sometimes isolated, with limited security systems, and the necessity to remain relatively open to the public, churches and other places of worship are very vulnerable. Moreover, there has always been a high demand for religious artefacts of different kinds on the art market. In some European countries, churches are the first victims of thefts.

Famous thefts from museums may make the newspapers’ headlines but their overall number has significantly decreased over recent years. Nevertheless, the creation of hundreds of new museums in emerging countries may pose new challenges in terms of collections’ security in the years to come.

Private houses are also frequently victims of thefts, most of the time from expert burglars who target specific pieces of art, as can be the case in museums and other places of conservation. The difference is that private owners often don’t have the required security to protect their pieces of art from such thefts.

Market vs. Sources countries

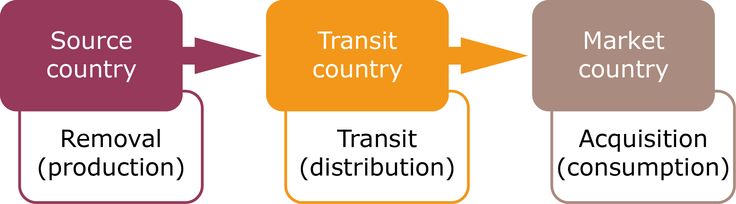

Illicit traffic in cultural goods is often organised through a common scheme: the removal from the place of origin, the transit and the acquisition. Within this scheme, one must also consider the specific distinction between three types of countries that we can qualify as:

- Source countries, from which the objects are removed

- Transit countries, through which the objects are transported and transited

- Market countries, in which the objects are bought, traded, or sold

The different characteristics of a source country:

- Difficulties (technical, human, financial) to ensure the protection of its cultural heritage, (particularly archaeological sites)

- Weak economy, which can encourage individuals or communities to participate in a lucrative traffic

- Richness of archaeological heritage and history

- Abundance of movable cultural property (including religious)

- Occurrence of a civil unrest, armed conflict or any other man-made or natural disaster. The Egyptian revolution (2011) or the Syrian armed conflict are perfect examples of how conflict areas can be suddenly exposed to greater risks and see occurrence of illicit traffic in cultural goods increase significantly

Given those criteria, developing countries are, in general, at greater risk of thefts and looting.

The existence of a transit country can be based on different factors, such as the geographical position between source and market countries, the presence of existing networks for various traffics and/or criminal organisations, and lesser control in merchandise shipping and receiving.

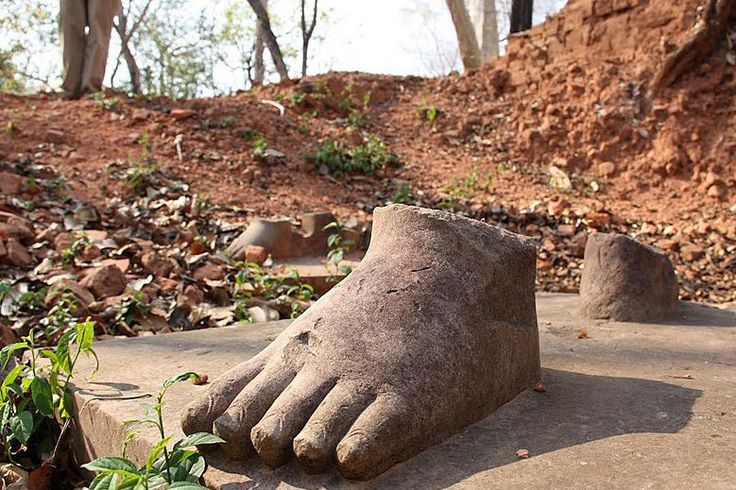

Feet of a looted statue, Koh Ker, Cambodia. Photo: Illicit Cultural Property

The market country:

A market country is not necessarily the country in which the object is sold, but the country of origin of the person buying the object. Market countries are naturally characterised by the existence of a strong demand for archaeological objects and in many cases a structured legal art market. Some objects can actually be sold several times on the black market, sometimes over the course of several decades, before emerging in a legal auction with what seems like valid property titles.

Finally, a weak national legal framework or a lack of implementation measures of the existing international law with regards to the trade of cultural objects are also a prime element in explaining the development of illicit traffic in cultural goods in both transit and market countries.

Although it is rare, certain countries presenting all these different characteristics can thus be considered both as market, transit and source countries, due to the issues of theft and looting their cultural objects face while at the same time being a hub for buyers of objects from either this same country or elsewhere.

Vermeer's The Concert, stolen from the Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, in March 1990. Photo: Wikipedia

A shifting market: from West to East, and back?

Objects are exported from a great number of places to a number of other places. North America and some countries in Western Europe were traditionally considered as the main market countries. Though these countries can remain destinations of choice for artefacts, the current market trend seems to modify this scheme: the market for cultural goods seems to have slowly been shifting towards the East. More Asian and Middle Eastern countries also actively participate in the art market, buying objects and importing them into their countries.

One of the reasons that North America and some Western European countries have seen a decline in their illegal trade is due to their reinforcement of national legislation, contributing the a better implementation of international legislation such as the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.

The market for antiquities moves and evolves as much as other art markets (contemporary, modern, etc.). The current trend seems to indicate that the legal traffic of cultural goods has reached Far East and Middle Eastern countries, and with this shift in legal sales the illicit market follows suit. An illicit traffic in cultural goods evolves in parallel to the legal market, as part of the basic offer-and-demand rule.

The case of conflict areas

Thefts of cultural objects take place all over the world, unfortunately, and not only in conflict areas or economically challenged countries. The growing media attention on the subject of illicit traffic would seem to indicate that only countries within these two types of regions are affected, though we know this to be untrue.

Though there has been a particular rise of such regrettable acts in the years 2011, 2012 and 2013, due in part to the military conflicts that have taken place and due in other part to the increased awareness and interest shown by the media and the general population, what would seem to be a “rising trend” in theft and traffic may actually be a “rising awareness” of the issue. From being considered as merely a simple case of theft, robbing of archaeological or ethnological objects from sites or museums are slowly being considered by the public opinion as a serious crime that not only contravenes the law but also ethics.

That being said, countries in conflict areas are particularly vulnerable. General chaos or the specificity of the conditions within countries affected by a conflict makes it so that fewer resources, such as guards, can be provided to sites and museums, thus facilitating the work of looters and thieves, whether they are criminals, members of the local population or soldiers from all sides.

A U.S. military tank takes a position outside the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad in an April 16, 2003. Photo: National Geographic News

Glossary: antiquity, archaeological heritage, archaeological site, auction, cultural heritage, cultural object, ethics, illegal trade, illicit excavation, illicit market, illicit traffic, implementation, import, inventory / registry, looting, movable cultural heritage, origin, provenance / provenience, smuggling, underwater heritage, valid title