Tourists, random buyers and other ill-informed individuals

Often unsuspected, tourists and other random buyers can easily be implicated in illicit transactions of cultural goods, a phenomenon aggravated by the rapid growth of mass tourism during the last two decades.

These same tourists, given their inexperience as art and antiquities buyers, are easy targets for dealers offering stolen or illicitly excavated cultural goods. Knowingly or not, such occasional buyers can easily find themselves involved in fraudulent sales, use of forged documentation and other frauds. Even though they are breaking the law, these buyers are often the good-faith victims of their own limited knowledge of the law and the basic administrative requirements regarding transactions involving art and antiquities.

Souvenir shop at Epidaurus, Greece. Photo: Virtual Tourist

Local communities

The difficult economic situation prevailing in many developing countries is the first factor in local communities’ involvement in the supply chain. In many regions of the world, as it is the case in several Latin American countries (an act known as “guaqueria” in some of countries within this region) or more recently in Afghanistan for example, members of local communities may turn to looting and selling of archaeological objects for obvious financial reasons.

Most times at the starting point of the traffic route, local communities rarely sell at high prices the archaeological artefacts which they have personally excavated.

Huaquero presenting a finding. Photo: Trafficking Culture

Individual criminals with financial purpose

One of the particularities of illicit traffic in cultural goods is its profitability, often described as a trade with maximum profit for minimum risk. Inappropriately indulgent legal sanctions, along with an abundance of cultural goods that can be stolen or looted and later smuggled, make this illegal activity very attractive for people already involved in other types of crimes.

Be they thieves, looters or simply the middlemen, operating only occasionally or experienced in the illicit market world, criminals can be easily attracted to this lucrative activity. Nevertheless, it is difficult to try to draw a single portrait of the criminals involved in illicit trafficking in cultural goods. Their different profiles in terms of criminal background, level of involvement or experience vary as much as their sources, markets and networks.

Crime investigation after the theft of several famous paintings at the Paris Museum of Modern Art. Photo: DR

Organised crime

According to the broad definition provided by the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, all international cultural property trafficking is a serious offence that is considered as organised crime as long as it involves a group of three or more people.

The role of mafia-type organisations in cultural property crime is a different question. Experts and law enforcement officers have always suspected connections (sometimes occasional) between such criminal groups and illicit trafficking in cultural goods, the logic being that the use of previously existing criminal networks, set up for a diverse range of illicit trades, could also be applied to the transfer of looted or stolen cultural property. Unfortunately, the lack of appropriate specific data and analyses has so far made this connection difficult to assert.

In Italy for instance, despite the long experience in this regard and the expertise of their Carabinieri unit for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, it is impossible to attest to a strong and long-term connection between the traffic of cultural objects and the mafia-like organisations. Experience shows that criminal networks are often limited in their number of members and that they operate at a smaller scale.

Yet, other parts of the world provide evidence showing a stronger connection with organised crime. In South-East Europe for instance, recent cases have shown a clear interaction between the transfer of stolen cultural goods and criminal groups involved in drug or weapon trafficking.

Member of Serbian police guard the stolen "The Boy in the Red Vest" painting by French impressionist Paul Cezanne, in Belgrade, Serbia, Thursday, April 12, 2012. Photo: Darko Vojinovic/Associated Press

Compulsive thieves

Cultural objects, particularly those with a high artistic, historical or symbolic value can also favour criminal impulses in people who would otherwise have no further motive to operate than the compulsive need to obtain a particular art or archaeological piece. The fact that compulsive thieves can be curators, guides or even random visitors acting opportunistically also make them very difficult to anticipate.

Private collectors

Private collectors are a key element in the wide spectrum of people associated with the illegal trade of cultural goods. Their involvement in the traffic sets two main difficulties for the organisations dedicated to countering it: the secrecy in which they often operate, and the weakness of the legal and ethical frameworks addressing their activity.

The situation has changed in these past years, due to the increasing control on sales and increased awareness of the need to proceed with detailed scrutiny and precautionary measures when acquiring a cultural object. Nevertheless, further action is required to encourage stronger ethical behaviour among the community of private collectors.

The convicted art dealer Giacomo Medici standing in front of the Trapezophoros with two griffins devouring a deer. Photo: Il Giornale Dell'Arte

Art market

For many years, the art market has been declared as one of the driving forces of illicit traffic in cultural goods, particularly in Western countries. Cases of stolen artefacts for sale in famous auction houses regularly made news.

Though financial interests, self-regulation and professional secrecy still prevail in the market, sometimes at the expense of ethics and control of legal provenience, the situation has dramatically changed in the past decade, at least among the leaders of the market. Public awareness, along with the accumulation of cases tarnishing the market’s reputation, has had very positive consequences on the profession, namely on the largest and most reputed auction houses.

Though the lack of due diligence remains an issue of concern within the market, the shift in attitude of major auction houses, along with the development of professional associations endowed with codes of ethics or conduct, have been a turning point in the recent past.

Unfortunately, in addition to a number of small auction houses with less consideration for the ethics of acquisition, the development of information technologies has been the source of a new rising trend in the art market: on-line sales. Internet has become an uncontrolled market place for stolen or looted cultural goods.

Scientists and academics

The role scientists and academics play in the development of the traffic is often underestimated or even completely disregarded, even though several articles have already highlighted the implication of members of academia in fraudulent transactions or other activities connected to illicit traffic in cultural goods.

Few codes of conduct for archaeologists or art historians actually mention the prohibition for scholars to support, directly or indirectly, illicit traffic in cultural goods. Scientists and academics may be involved in the traffic in many different ways: unregulated and unscientific excavations, sale of objects coming from legal excavations, transaction of looted artefacts, fake expertise or production of forged certificates.

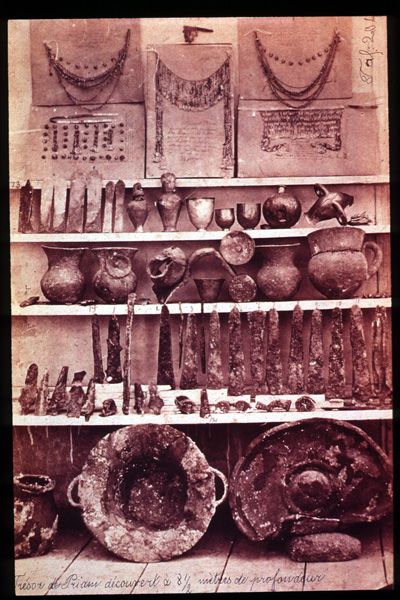

The Priam's Treasure, illegally taken from Troy in the 1870's by the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann. Photo: Wikipedia

Places of conservation

Though museums still are the first target of claims for return and restitution of cultural objects legally or illegally removed from their country of origin, their involvement in illicit traffic has dramatically changed in the past decades.

The development of ethical standards and strict rules of procedure in the museum world, along with the involvement of top-ranked museums in court cases, has deeply modified the institutional policy of acquisition. This is particularly so in Europe and North America, where tools and practices are being developed to ensure legal transactions of cultural goods. Museums can no longer be considered as a common destination for looted or stolen cultural goods, notwithstanding the fact that some members of the museum community may still not abide by the internationally recognised ethical standards such as the ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums.

Nevertheless, the current unbridled development of museum activities in certain parts of the world represents a new challenge for the international museum community in extending otherwise now widespread acquisition procedures and ethical standards.

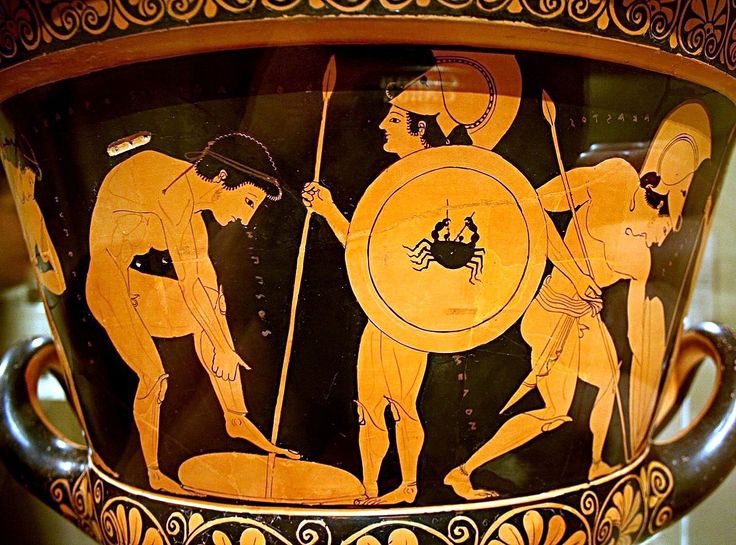

Euphronios krater, returned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to Italy in 2006. Photo: Wikipedia

Public officials, diplomats

Just as in the case of academics, the involvement of national and international diplomats remains a taboo and undocumented subject, and a sensitive aspect of the trend.

Several cases have already shown the use of diplomatic immunity and diplomatic channels for the easy import, export and transaction of cultural objects of doubtful provenience. In some countries, public officials have been also charged with producing and selling illegal authorisations of excavation.

Soldiers, military

History is full of examples proving the high vulnerability of conflict areas to thefts and looting, given the lack of protection granted to cultural heritage in these particular contexts.

In this respect, different reasons can encourage military personnel from all sides, and both national and foreign, to participate in the illicit trafficking of cultural property. Cultural objects are first and foremost sold for the source of revenue they can represent to soldiers, whether they are stolen randomly or upon specific order. But they can also be kept as a “souvenir”.

The plundering of a country or region’s cultural property can also be part of a military strategy consisting in the destruction of the symbolic value of the enemy’s cultural heritage.

In this area too, times have changed and progress has been made thanks to the promotion of standards and training manuals for the protection of cultural heritage in conflict, as is the case for the US Army for example.

General Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, inspects art treasures hidden in a salt mine in Germany. Photo: Wikipedia

Private companies

In the particular case of the looting of underwater archaeological sites, several cases have proven the involvement of private companies initially involved in drilling operations or other kinds of legal underwater activities.

Some have been commissioned by the State to specifically search for underwater heritage, with the aim of sharing the findings and saving the wrecks. In this case, companies have been sometimes known to keep hidden part of the findings to illegally sell them in other countries and/or via internet.

Glossary: acqusition, antiquity, archaeological object, auction, certificate of authenticity, code of ethics, collection / collector, cultural good, cultural property, curator, due diligence, ethics, expertise, fake / forgery, good faith, guaquero, illicit excavation, illicit export, illicit import, illicit market, illicit traffic, internet sales & auctions, looting, plunder, provenance / provenience, restitution, return, underwater heritage